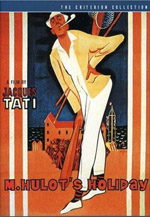

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday

Winner of the Golden Palm at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival, Mr. Hulot’s

Holiday is my favorite of the many Jacques Tati films that I have seen. As

director, co-author, co-producer and star, Jacques Tati tells, in his peculiar,

quirky and eccentric style, the story of a group of ordinary people trying

desperately to enjoy themselves while on summer vacation at the beach. Having

just gotten back from a vacation in Door County, I can relate perfectly. Luckily

for us common folk who fumble and stumble our way through these holiday

misadventures, Jacques Tati is sympathetic to our plight. As the

well-intentioned but forever-in-trouble Mr. Hulot, Jacques Tati shows us keen

observations of human foibles without being judgemental or turning a blind eye

to our shortcomings.

Winner of the Golden Palm at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival, Mr. Hulot’s

Holiday is my favorite of the many Jacques Tati films that I have seen. As

director, co-author, co-producer and star, Jacques Tati tells, in his peculiar,

quirky and eccentric style, the story of a group of ordinary people trying

desperately to enjoy themselves while on summer vacation at the beach. Having

just gotten back from a vacation in Door County, I can relate perfectly. Luckily

for us common folk who fumble and stumble our way through these holiday

misadventures, Jacques Tati is sympathetic to our plight. As the

well-intentioned but forever-in-trouble Mr. Hulot, Jacques Tati shows us keen

observations of human foibles without being judgemental or turning a blind eye

to our shortcomings.

Filmed in black and white at Saint-Mar-Sur-Mer, Brittany and Saint-Marc-Sur-Mer, Loire-Atlantique, France, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday presents broad caricatures of various character or personality types. If there is comic genius behind this work, it would be the manner in which the vacationers in the movie seem more real to us, by the film’s end, than characters in a thousand other so-called real life dramas. The characters in the film are not presented to be lovable, but we do recognize ourselves without feeling worse for it. The original music by Alain Romans is terrific and has a sweet longingness to it. There is also a very touching, nostalgic poignancy to the film’s end. Jacques Tati’s style may not work for everyone, but it’s impossible not to appreciate and admire the creator of such inspired lightheartedness.

Greg Postles

Whitefish Bay, WI

Whitefish Bay, WI

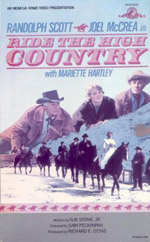

Ride the High Country

One evening about fifteen or twenty years ago I walked six or eight blocks to

the Oriental Theater in Milwaukee to see Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch.

I had no intention of seeing the second feature, Ride the High Country ,

but, at the last minute, I decided to stay. Am I glad I did. Ride the High

Country was only the second movie directed by Sam Peckinpah, and is now

regarded as perhaps his finest film. In it, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott play

aging former lawmen, who are hired to transport gold out of a mining town in the

High Sierras. After having made nearly two hundred movies between them, this was

to become Randolph Scott’s last movie and Joel McCrea’s second to last. Ride

the High Country also marks Mariette Hartley’s first film.

One evening about fifteen or twenty years ago I walked six or eight blocks to

the Oriental Theater in Milwaukee to see Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch.

I had no intention of seeing the second feature, Ride the High Country ,

but, at the last minute, I decided to stay. Am I glad I did. Ride the High

Country was only the second movie directed by Sam Peckinpah, and is now

regarded as perhaps his finest film. In it, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott play

aging former lawmen, who are hired to transport gold out of a mining town in the

High Sierras. After having made nearly two hundred movies between them, this was

to become Randolph Scott’s last movie and Joel McCrea’s second to last. Ride

the High Country also marks Mariette Hartley’s first film.

A number of things stand out in this movie as exceptional. The cinematography by Lucien Ballard is gorgeous. It is hard to recall a movie where mountains and lakes and aspen trees, and even the grittiness of the mining town, are captured so beautifully. The screenplay presents a variety of emotionally complicated issues in a manner that is simple, sensitive and humane. For instance, Edgar Buchanan, in a fine role as the drunken mining town judge, delivers a wonderful oration on marriage, but does so while presiding over a wedding that is taking place in a whorehouse. The strange contrast makes the speech all the more compelling and unforgettable. The musical score, in keeping with the themes and mood of the movie, is appropriately sad and nostalgic.

Finally, this movie is about two underappreciated and underpublicized actors, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott. Released in 1962, Ride the High Country originally cast the two stars in the opposite roles than the ones they ended up in. Independent of one another, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott each went to the movie’s producer and suggested that they would be more convincing playing the other actor’s part. In the end both men got their wish. What was ultimately accomplished was that issues of simple right and wrong are explored without seeming false or preachy, and issues about aging are presented simply and sympathetically. The last scene in the movie is one of the most famous in movie history, and will leave you a Joel McCrea fan for life.

Greg Postles

Whitefish Bay, WI

Whitefish Bay, WI